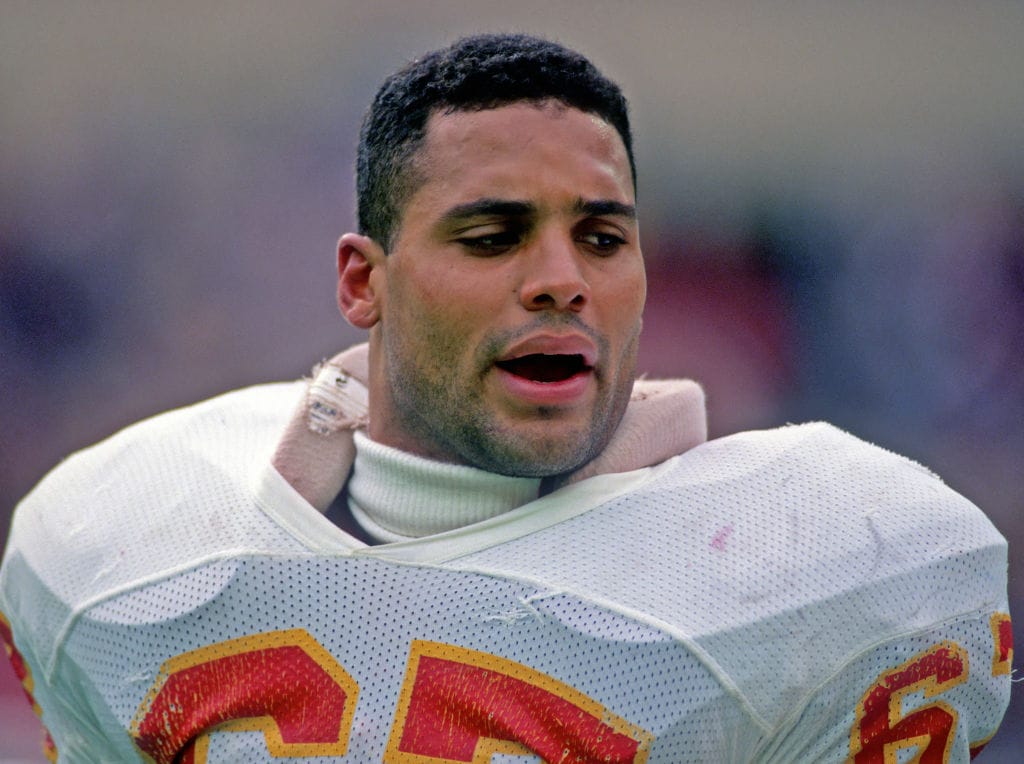

At 6 feet, 7 inches tall and 235 pounds, Art Still is quite a big guy. And that’s down from the 275 to 280 pounds he used to weigh — before the symptoms of amyloidosis became increasingly apparent.

Still, 69, is a former NFL defensive end. And now he’s a foot soldier — along with cofounder Mike Lane — in the Amyloidosis Army, a nonprofit group that raises awareness about this obscure yet life-threatening disease.

Amyloidosis is an accumulation of amyloid, which is a protein produced in bone marrow. Although amyloid can collect in any organ, when it accumulates in the heart, the buildup prevents the heart from filling with blood; it also causes an irregular heartbeat.

Transthyretin amyloid cardiomyopathy (ATTR-CM) can be a form of hereditary ATTR amyloidosis (hATTR), which has a median survival of 10 years after diagnosis. Patients with the much more serious form of the illness, wild-type ATTR-CM, live on average 3.5 years after diagnosis.

In general, the disease is quite rare, though certain ethnicities are especially vulnerable. The T60A variant of the TTR gene affects 1 in 100,000 people of Irish and English descent, while the V30M variant affects 1 in 538 people of Portuguese origin, and V122i strikes 1 in 25 African Americans. Men are more likely to get amyloidosis than women, and it usually develops between ages 60 and 70.

“There’s a lot of serious sickness in my family. When I start looking at my mother’s history and my father’s history, there’s been heart problems, stomach problems, loss of appetite, that sort of thing,” he said. “If I had heard about amyloidosis a long time ago, it would have been a different story, because I’m always Googling things. But back then, the information wasn’t out there.”

March is National Amyloidosis Awareness Month, noted Still, who spoke to Rare Disease Advisor — a sister brand of ATTR-CM Companion — by phone from his home in Kansas City, Missouri. And raising awareness is crucial, he said, because more than 1.6 million African Americans may unknowingly carry the V122i variant, leading to heart failure.

Listen to a Rare Disease Advisor podcast with Art Still

The future star athlete was raised with his five sisters and four brothers in a low-income neighborhood of Camden, New Jersey, across the Delaware River from Philadelphia.

“We were poor people. The only way of getting out of the city was by means of my athletic skills,” he said.

Still excelled in high school football, earning him a scholarship to the University of Kentucky. In 1978, the Kansas City Chiefs drafted him in the first round. For 10 years, he played defensive end for the Chiefs, then moved to the Buffalo Bills for another 2 years.

“Throughout my career, I had injuries here and there,” he recalled. “In 1990, after I retired from the NFL, I was going through my medical records. I had some surgery done on my shoulder, and my doctor — after doing the repair work — told me, ‘don’t be surprised if you have a bicep tear.’ Within a year, I did have a bicep tear, and that’s one of the symptoms of amyloidosis.”

Soon after that, Still started developing other symptoms consistent with ATTR: neuropathy, back problems and carpal tunnel syndrome. And for more than a decade, he knew he had an irregular heartbeat. But as a pro football player, he tried to reason it all away.

“You figure you’re going to have some type of negative effect from constantly hitting on people. This what happens when you beat your body up for 20 years,” he said. “Then you put aging in there too, and you think to yourself, ‘my feet are swelling up. Maybe I’m just getting old.’”

Still never did anything about the irregular heartbeat. But he eventually took advantage of a wellness program offered through the NFL Player Care Foundation. In September 2023, he got a thorough checkup at Tulane University School of Medicine; that’s when he was diagnosed with amyloidosis.

“On the third and last day, they called my wife in to tell her that I had some serious health problems with my heart,” he said. As it turns out, Still’s older brother, “Sparky” James, had had a heart transplant 14 years earlier after experiencing the same symptoms. And his son, Jahmai, who died at the age of 36, had both amyloidosis and sickle cell disease.

“I’d seen him go from doctor to doctor. He got surgeries on his knees, his back, his hands. He took medication that then affected his heart, so he needed ablations,” Still said. “He had so many ablations on his heart that they couldn’t do any more. He had to have a heart transplant.”

A subsequent genetic test ordered by Dr. Brett W. Sperry, Still’s cardiologist in Kansas City, confirmed that Still had ATTR-CM. It was Dr. Sperry who put Still in touch with fellow amyloidosis patient Mike Lane, who has the Irish variant of the disease. Together, both men formed the nonprofit Amyloidosis Army.

Still has 11 children — 6 sons and 5 daughters — plus 25 grandchildren.

“You’ve got to be the best advocate for yourself,” he said. “You know your problems. You know your issues. They say wives save lives and that’s so true, because when a doctor asks men about our problems, we’ll say ‘oh, I’m alright.’ And she’ll say ‘no, he’s not alright.’ A lot of doctors are not aware of amyloidosis, so they’ll treat only the symptoms.”

Other athletes in Still’s “army” include Hall of Fame basketball star Nate Archibald, who played 14 seasons in the NBA, mostly for the Boston Celtics; fellow Celtics player Don Chaney, who also coached the Houston Rockets; and football star Pete Shaw, who played for the San Diego Chargers and New York Giants.

Among other things, the charity offers free presentations to predominantly Black social and civic clubs, senior centers, retirement communities and churches. It focuses specifically on the V122i variant, and it urges increased awareness for early detection as well as timely intervention.

“We’ve found out that this works much better, because people are more apt to talk to you when you’re telling your own story,” Still said. “It’s a shame that we live in a world that shade of color or where you’re from has a bearing on health. It shouldn’t, because we’re all human beings.”